We all know exercise is good for us – it helps us lose weight, reduces blood pressure, and increases our fitness levels, which in turn decreases our chance of strokes, heart attacks and premature death. It also makes us feel good.

So why aren’t we all doing the currently recommended prescription of 30 minutes of aerobic exercise per day, 5 times per week?

Firstly, because this isn’t a realistic option for most people, who have other demands on their time, and may also not possess the equipment, facilities, finances or motivation. Secondly, humans are not logical; we will usually seek the path of least resistance, discounting future benefits (health and longevity) for more immediate ones (pizza and beer).

Traditional endurance exercise prescriptions may well be quite effective, but the reality is that telling people to do 30 minutes of exercise per day, 5 days per week is not helpful, without a major shift in our cultural attitudes and behaviour.

Having said that, there’s an urgent need to incorporate movement and exercise into our daily lives to address the growing obesity and inactivity pandemic.

So what if we could improve our fitness and health by doing simple exercises at home for less than 30 minutes per week?

This is the enticing prospect offered by High Intensity Interval Training (HIIT), a shorter, more intense version of traditional interval training, which dramatically reduces the time necessary to achieve meaningful health benefits.

It sounds like a fad, but there’s a growing body of evidence which suggests that it can be effective. Equally importantly, it offers a realistic approach to getting people moving.

So what is HIIT?

High Intensity Interval Training is generally taken to mean repeated bursts of high intensity exercise at or approaching maximal effort, with short periods of rest or low intensity activity in between.

An typical example of a lab based HITT session might involve cycling all-out for 30 seconds followed by 4 mins of recovery, repeated 5 times. This is repeated 3 times per week for 2 to 6 weeks. This equates to 2.5 mins of intense exercise per session and 7.5 mins per week.

Obviously the total exercise time is somewhat longer when you factor in warm up and recovery times, but is still considerably less than the currently recommended 150 mins per week.

These very low volumes of high intensity training have been shown to improve not only cardiorespiratory fitness, as measured by a persons VO2 max, but also metabolic health, as measured by ones glucose control.

What is VO2 max and why should we should care about it?

VO2 max is a person’s maximal oxygen consumption. It can be estimated by putting someone on a treadmill or cycle ergometer and measuring their peak work rate achieved.

It represents your ability to transport oxygen from the atmosphere to your muscles to perform physical work. A chain of events are involved in this process, which involves the lungs, heart, blood vessels, skeletal muscle cells and mitochondria. So V02 max can be thought of as a marker of total body health.

A low VO2 max is associated with heart disease and death, and is a marker of poor health in the same way as traditional risk factors such as smoking, high cholesterol, high blood pressure and type 2 diabetes. On the other hand, small improvements in VO2 max are associated with significant improvements in mortality, with the largest benefits being seen at the low end of the fitness spectrum.

It has even been suggested that VO2 max should be measured routinely in health checks in the same way as other vital signs such as heart rate, blood pressure, weight etc.

Does HIIT actually work? What’s the evidence?

A growing body of research exists to support the effectiveness of HIIT in producing beneficial physiological changes in the cardiovascular, metabolic and skeletal muscle systems, even after short periods of low volume training.

A number of such studies have come from McMaster University in Canada (for example see here and here). They suggest that HIIT regimes can be as beneficial as traditional endurance training in improving exercise performance and other markers of health (VO2 max, blood pressure, insulin sensitivity), despite involving considerably less time commitment.

However, there are limitations to the general applicability of this research, because to date, the studies generally involve short term, laboratory based training programmes on small groups of young, active people.

And many questions still remain unanswered, such as the optimal intensity and volume of HIIT regimes to achieve worthwhile benefits, whilst still being practical and tolerable to the average person.

How low can you go?

The investigators at McMaster compared a very brief HIIT protocol with a traditional endurance protocol. The HIIT regime involved 3 lots of 20s sprints on a cycle ergometer, within a 10 minute session including warm up and cool down. The traditional endurance regime consisted of 50 minutes of moderate intensity cycling. The sessions were performed 3 times per week over 12 weeks. Markers of cardiometabolic health (V02 max, insulin sensitivity, muscle mitochondrial content) improved to the same extent in both groups.

Martin Gibala, a professor of Kinesiology at McMaster, who is responsible for a number of studies on HIIT, suggests that the one minute protocol described above (3 x 20s sprints), is likely to be the lowest effective workload. Indeed this has led to him co-writing a book on HIIT, teasingly entitled the One Minute Workout.

A recent meta-analysis (research which combines data from similar studies) suggested that sessions involving even fewer sprints (e.g., 2 rather than 3) are associated with greater improvements in vo2 max.

So how do the likes of you and me put it into practice?

Most of the studies on HIIT involve sprints on a cycle ergometer or treadmill. I don’t possess either of these and have no desire to, and neither, I imagine, do the majority of people. I’m also not a gym goer, although I appreciate many people find them useful. The whole point of doing HIIT, as opposed to more traditional exercise, is, in my opinion, that it offers a solution to the barriers that prevent many people exercising in the first place, namely time, money and opportunity.

So we need more pragmatic solutions for engaging in HIIT.

One option would be to simply work interval training into your daily routine. For example, if you are out walking then you could simply pick up the pace for short periods, or walk up hills, or take the stairs more often.

Alternatively, the method I’ve found to be interesting and practical is High Intensity Circuit Training (HICT) – there’s no special equipment required here, it can be performed anywhere, using body weight as resistance.

Probably the best known example of a HICT regime is that designed by Brett Klika and Chris Jordan, who published this practical article in the American College of Sports Medicine’s Health and Fitness Journal. Their seven minute workout was popularised by the New York Times and has spawned a number of apps which guide you through the circuit.

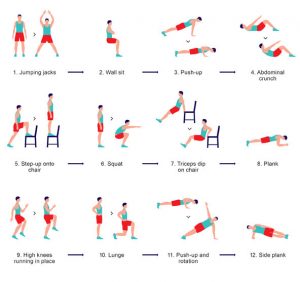

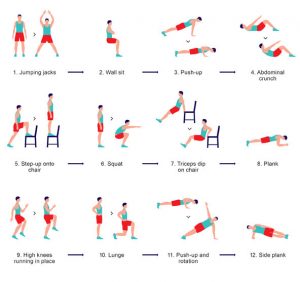

Their workout combines both aerobic and resistance training in a series of exercises that takes 7 minutes to complete. The circuit consists of 12 stations, designed to exercise all the major muscle groups and achieve a balance of strength throughout the body. Ideally they should be performed in the following order to allow opposing muscle groups enough time for recovery:

- Jumping Jacks

- Wall sit

- Push ups

- Abdominal crunches

- Step ups

- Squats

- Triceps dips

- Plank

- High knees running on the spot

- Lunge

- Push ups with rotation

- Side plank

Each exercise is performed for 30 seconds at maximum intensity, doing as many reps as you can, with 10 seconds of rest between exercises.

Does it work? The bulk of the evidence for the benefits of HIIT compares sprint interval training using cycle ergometers with more traditional moderate intensity endurance training. I’m not aware of as many studies that compare low volume high intensity circuit training (ie. 7 minute workouts) to more traditional workouts (but here’s one). However, provided you’re exercising fairly vigorously there seems no reason why HICT shouldn’t provide similar benefits in terms of cardiorespiratory fitness.

Purely anecdotally, I’ve been doing HICT for a few months now and subjectively I’ve noticed improvements in my fitness levels. By that I mean, the exercises now seem much easier and I can push myself harder, to the extent I’ve started substituting some of the easier exercises for harder ones (e.g. lunges —> jumping lunges, plank —> mountain climbers, jumping jacks —> burpees).

So what are the pros and cons of HIIT?

HIIT is certainly a time efficient form of aerobic exercise and studies suggest that it’s effective at improving cardiorespiratory fitness and insulin sensitivity.

However, we should keep in mind that these are generally small, short, lab based studies on younger people without significant health problems, so we shouldn’t over-extrapolate the findings.

It’s also not immediately obvious how best to maintain interest and make progress in the long term, once you’ve reached a certain level of fitness. How do you modify the regime? More circuits? Longer sprints? Less recovery time?

Nonetheless, despite these issues, anything that helps people to get moving and exercise regularly is a really exciting prospect both for individuals and at a public health scale.

HIIT is not going to appeal to everyone however, and there will be some people who are put off by the discomfort involved. That’s fair enough – exercise should be enjoyable, not unpleasant. There are plenty of other options around. HIIT is by no means the only game in town, it’s just time efficient.

Experiment and find an activity that interests and excites you. Or try and incorporate exercise into your daily routine – taking the stairs, walking or cycling to work, run on the spot while you’re waiting for the kettle to boil, chase around after your kids/ grandkids.

Finally, because of the high intensity nature of this type of training, it’s really important for anyone who is overweight, deconditioned, elderly, injured or with comorbidities such as high blood pressure or heart disease to seek medical advice before starting HIIT. While these are the groups that could potentially benefit most, it’s crucial that they approach HIIT in a sensible, graded way, tailored to their needs and background.